Van Gogh himself had admitted to finding few things more invigorating in art than a sense of mastery. Why then, wondered Mary Oliver, did she feel only doubt and a dull sense of déjà vu, as if she were repeating herself.

Draining a bottle of Ravenswood merlot, she swatted her cat from the stack of mail and returned to her letter to her dear friend, Senator Hillary Clinton: “My robes, Hillary. Once a clear and accessible metaphor for wisdom, tonight my robes suggest only mothballs and Marlboro Reds. . . .”

Some dark, forgotten hours later, Mary found herself alone, undraped, her feet in damp seaweed and her face in the stars, recalling with some indignation that Saturn’s rings, though they may look continuous, are actually composed of innumerable small particles. “What’s more,” cried Mary, fists raised to the heavens, “your rings are extraordinarily thin. They might be some 250,000 km or more in diameter, but they’re only .9 km thick, at most!” Motor skills ever more sluggish as she switched unconsciously between adjectival interpretations of the word, “nine,” and the mathematical abstraction it represented, Mary crawled to the foot of the moonlit dunes.

Earlier that evening, watching a documentary on Stephen Hawking, she had drawn comfort if not some inspiration from the knowledge that the laws of science did not distinguish between the forward and backward directions of time. Now, however, the thought nauseated her, as did the wrenching recollection that at least three arrows of time dodistinguish the past from the future: the thermodynamic arrow, the direction of time in which disorder increases; the psychological arrow, the direction of time in which humans remember the past but not the future; and the cosmological arrow, the direction of time in which the universe expands rather than contracts.

“It’s not enough!” choked Mary, her voice lost in sand, in surf, in what seemed an endless spinning void spattered with a blur of stars. “A poets needs a rubric, a formula, a code. We need specific descriptions . . . expectations . . . how a poem should look . . . sound. . . .” And then, mid-prayer, clinging to a bit of driftwood, head tucked down, legs pulled in tightly, Mary began to snore.

* * *

Come morning, a border collie patrolled the beach, attempting to corral stray terns, while Samuel Amadon, courtesy of the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, sat high on a dune, observing both the collie and the sleeping, naked Mary Oliver. Sam was not alarmed that his time on Cape Cod had yet to yield a poem. He had, after all, made several lists. His favorite was Taffy Flavors, though his list of Beach Garbage was also quite delicious. He thought he might call these “indices,” however, rather than “lists,” as “indices” evoked the authority necessary to offset the playful nature of his work. He decided to dedicate the taffy index to Bhanu Kapil, the garbage index to Juliana Spahr. Sam enjoyed including other people’s names in his work, on the chance that his friends and family would be inspired to check them out. Why not, he figured—Mary Oliver already had plenty of people checking her out: in this case, one third of Cape Cod’s nine local people of color, taking a stroll before work, now staring in silence as Mary, cursing God, extricated the spines of a horseshoe crab from her pruned and salty ass. It appeared to Sam that the Limulus polyphemus resisted personification even in death, resisted poetry altogether. Finding no mention of the horseshoe crab in Spahr’s wrenching litanies of endangered lives, nor in the volumes of Jeffrey Skinner’s groundbreaking and increasingly important journal, ecopoetics, Sam decided to turn away from poetry, at least for the moment, to read instead a bit of non-fiction regarding the horsehoe crab, wherein, without the benefit of another human’s epiphany, he was able experience his own: he could do his part to help members of the four remaining species survive, simply by flipping them over, should he find them struggling on their backs.

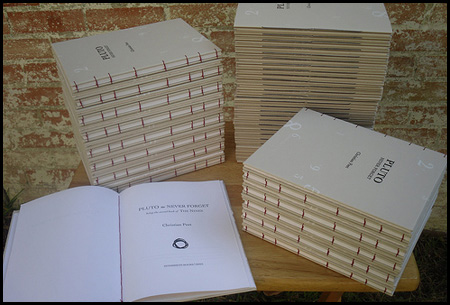

© 2008 Christian Peet. Published in the chapbook, Pluto: Never Forget (Book II of The Nines), from Interbirth Books. Originally published in Denver Quarterly.

© 2008 Christian Peet. Published in the chapbook, Pluto: Never Forget (Book II of The Nines), from Interbirth Books. Originally published in Denver Quarterly.