When Cleopatra determined that her apple had been both genetically modified and irradiated, she may have compared it to a summer’s day. Or she may have compared it to Uranus: holding the apple on its side, she may have noted how both the stem and the opposing, bark-like nub of the seed core are not unlike the abnormally tilted axis of said planet. She may have recalled, too, that at the time of Voyager 2’s passage, Uranus’ south pole was pointed almost directly at the sun, as if engaged in this egregious mix of metaphors as a show of disrespect: mooning, as it were, the sun. If inspired, she might have spun this cosmological event into the realm of myth: the genesis of a new religion, perhaps; or, at least, an addendum to the literature of the tribes, explaining the difference between two peoples, they who mooned Sun and they who did not—the latter being pleasing to Sun, who in turn promised the tribe His love and protection, as well as a patch of salt and sand on the shore of the Dead Sea, to call their own. Cleopatra suspected that she could do worse than offer a stirring account of this tribe, in the form of mass-market paperbacks and a supporting lecture series. “Even in the nascent 21st century,” wrote Cleopatra, in the margins of A Brief History of Time, “some twelve thousand years after the earliest stories of the Hebrew scriptures, polarizing allegories remain popular sources of both personal pride and political policy.” Returning to Hawking’s discussion of the expanding universe and the “troublesome no-boundary condition,” she underlined the sentence that first gave her pause, then caused her to drift: “Conditions suitable for intelligent life can exist only in the ‘expanding’ phase of the universe.”

“Huh,” said Cleopatra to the Nubian goat nuzzling the side of the warm hay wagon in which she sat. “How long you reckon the universe has been shrinking, anyway?”

The goat turned to Cleopatra’s voice, its own mouth full of straw.

“Don’t worry,” said Cleopatra. “It won’t be on the test. Anyway, I’m done with essays for now. I’ve switched to short fictions.”

In the breast pocket of her flannel shirt, Cleopatra’s cell phone vibrated intermittently. The Caller ID screen read “Virtuous Pagans.” Someone in the small circle to which Cleopatra belonged—local organic farmers, fiber artists, gender activists, Wiccans, yogis, et al—was calling from Headquarters.

The code was simple but effective—precisely, reasoned the Pagans, like the architects of the Patriot Act.

“Hola,” said Cleopatra.

“Much can be seen from a car, bus, train, boat, or airplane,” said the caller.

“Yes—but intensive looking usually involves some walking,” replied Cleopatra.

“Monet . . .” intoned the caller, leaving a pregnant pause.

“Was the real inventor of Intuitionism,” came the reply.

Cleopatra powered off the phone and slipped it back into her pocket. More than a bit unnerved, she sat up straighter and inhaled deeply through the nose. She bent her left leg inward and crossed her left ankle over her right. “It’s time,” she said to the goat. “Salmon may not know what they do or why, but they know to swim upstream—and so do I.”

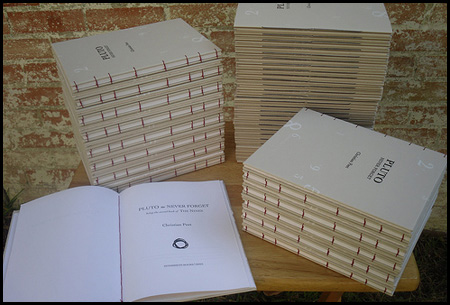

© 2008 Christian Peet. Published in the chapbook, Pluto: Never Forget (Book II of The Nines), from Interbirth Books. Originally published in Denver Quarterly.

© 2008 Christian Peet. Published in the chapbook, Pluto: Never Forget (Book II of The Nines), from Interbirth Books. Originally published in Denver Quarterly.