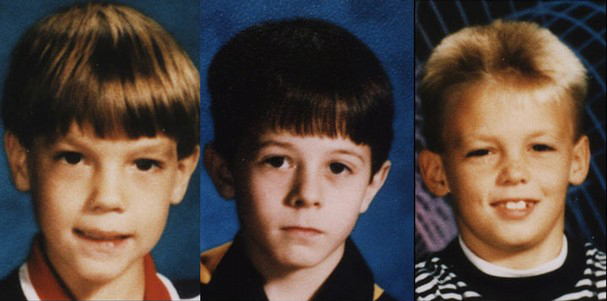

Among the chosen few who can understand all but one aspect of Pam Hicks’s grief are the parents of the other two boys murdered that night in 1993: Mark Byers, the father of Christopher Byers, and Todd and Dana Moore, the parents of Michael Moore. [For more about Pam Hicks, see also The “Other” West Memphis Three(1): Ain’t No Thing]

Mark Byers, like Pam, originally believed the story provided him by West Memphis and Arkansas authorities.

He no longer believes it.

In the absence of a new story, however—or, more to the point, in the absence of authorities catching a new killer or killers—Todd and Dana Moore, at the time of this writing, continue to believe the State’s official story.

In addition to being joined by their losses—regardless of whom they believe responsible for the deaths of their sons—Pam, Mark, Todd, and Dana share another thing in common: they have been wholly abandoned by West Memphis and Arkansas authorities.

For its part, major media appears to have forgotten not only the victims of the 1993 murders, but also their parents and everyone who loved them.

In the last several months, there has been no shortage of “new” articles on the “West Memphis Three,” but the vast majority detail cast additions and changes to Atom Egoyan’s forthcoming fictional film based on the very real unsolved murders.

Sadly, Atom Egoyan’s fictional film, Devil’s Knot, not only shares a title with Mara Leveritt’s excellent nonfiction 2002 book on the subject, but more than displeases the real Damien Echols, who suffered just shy of two decades on a very real Death Row for the crimes that Egoyan now intends to fictionalize. 17 [See The “Other” West Memphis Three: Loser Occult]

Families of the victims of those crimes can only hope that Egoyan’s film will mean a second-coming of star-power–such as freed Damien, Jason, and Jessie–but this time to assist Arkansas authorities in investigating who in fact murdered Stevie Branch, Christopher Byers, and Michael Moore.

For their part, the now-international legal, celebrity, and grass-roots defense team for The West Memphis Three, along with anonymous donors, offers a cash reward for information leading to the arrest of the real murderer(s).

That said, to be clear: it’s not the job of the WM3 Defense also to solve the case of “The Other West Memphis Three.” It certainly is not the responsibility of Damien, Jason, and Jessie, who–need it be said–owe nothing to anyone.

No. The job of solving this case, or at the very least admitting they have not solved the case, while exonerating the WM3, remains with State of Arkansas authorities as it has for almost twenty years.

As they say, Nothing’s changed in that department.

ELLINGTON V. MCDANIEL

On the day of “the plea that freed the three,” Attorney General Dustin McDaniel, either out of ignorance or contempt for his responsibility to the state he serves, issued to media the following jaw-dropper:

Since the day of their original convictions, the Attorney General’s Office has been committed to defending the guilty verdicts in this case.18

Apparently we are to understand that, for McDaniels, justice for victims takes a back seat to his saving face.

But McDaniel—against whom journalist Mara Leveritt also sought official discipline “for not taking affirmative action in response to evidence of juror misconduct” in one of the WM3 trials, and whom Leveritt would later sue19—also made clear that whatever came of the plea agreement, it’s Prosecutor Scott Ellington’s doing.

“As Attorney General,” McDaniel continued, “I always respect the discretion and judgment of elected prosecutors. Prosecutors know their cases better than anyone.”20

Indeed. Luckily for all involved, that prosecutor is now Ellington, rather than the now-infamous Fogleman, or McDaniel himself.

WITNESSES FOR THE STATE: DANA AND TODD MOORE

While Pam Hicks and Mark Byers stopped believing the State’s “official” story years ago,21 Dana and Todd Moore continue to hold tight, understandably, if heartbreakingly, to the small comfort offered by that fiction.

In December 2011, however, a different sort of movie-centered news made the rounds—“Parents: No Oscar nod for film about Ark. Killings,” the title of one—all of which served to explain that the Moores did not believe the third installment of Berlignger & Sinofsky’s West Memphis Three documentaries should receive Hollywood’s biggest film award.22

Of course, this information came as “news” only to reporters and readers completely unfamiliar with the case. Nor was it terribly helpful for newbies to learn23.

Nevertheless, December’s hot news circulated around the globe: Dana and Todd Moore, who have long wished suffering and death on the murderers of their children—and were very public about their wishes, including in Berlinger’s and Sinofksy’s first film—also didn’t feel it right that these murderers, who in December 2011 were already “movie stars” in addition to having just walked out of prison, should now garner for Berlinger’s and Sinofksy Hollywood’s biggest award. “We appeared solely in the first film because the directors lied and told us their purpose was to protect children,” the Moores told reporters.24

On 19 August 2011, Dana and Todd Moore experienced something beyond their imagining: watching in sickness and horror as the State of Arkansas informed them and the rest of the world that the three men tried, convicted, and imprisoned for the murder of their child and his two friends, were about walk out of prison, free. Moreover, the convicts were being released from prison not because they had served their sentences—which ranged from life in prison to death row—but due to some confusing legal wrangling that even the State found difficult to explain with any accuracy, especially to Dana and Todd.

NEW PLEA, NEW TRAUMA

On August 19, as if the original trials had never occurred, the Moores thought, Damien, Jason, and Jesse stood there and asserted their innocence after which the State found them “guilty” and then sent them home..

Furthermore, because the case remained officially “closed,” the State was legally absolved of any responsibility to further investigate the murders of the children.

Until this sudden paradigm-shift and the nearly unfathomable legalese that defined August 19, 2011, the State of Arkansas had offered Todd and Dana Moore an entirely different story, and much simpler one: a story in which justice was served and the guilty were punished. In this story, although eight-year-old Michael Moore still would never return, would never get older, at the very least his murderers had been apprehended, convicted at trial, and handed sentences from which they would never walk away.

If not justice, the story had been, for the Moores, something.

It was also a story that had been under attack by what seemed nothing less than the combined force of the music, television, and film industries, almost since the beginning of the Moore’s nightmare. Nearly two decades of questions about the investigation and prosecution of the case—via journalists, books, documentaries, and thousands of supporters of the convicted killers, eventually including other parents of the murdered children—left Dana and Todd to wonder who cared about the “Other” West Memphis Three.

The Moores had try to build what remained of their lives around the story provided by the State. It was a story of “closure,” if not one of “healing.” A story that could be read as “ending” with life sentences for Jason Baldwin and Jessie Misskelley, and the eventual execution of Damien Echols.

And on August 19, the State of Arkansas took even that story away.

see also:

Background: West Memphis Today

The “Other” West Memphis Three(1): Ain’t No Thing

The “Other” West Memphis Three (3): Loser Occult

All posts on the West Memphis Three

NOTES:

[17] Damien Echols’s patience with Atom Egoyan extends so far distinguishing between award-winning journalist Mara Leveritt’s book of the same title, and Egoyan’s Hollywood fiction, by Tweeting the latter as “Devil’s Knob.” [See The “Other” West Memphis Three: Loser Occult]

[18] Max Brantley. “Dustin McDaniel puts WM3 call on prosecutor.” Arkansas Times. Aug 19, 2011. http://www.arktimes.com/ArkansasBlog/archives/2011/08/19/dustin-mcdaniel-puts-wm3-call-on-prosecutor

[19] Max Brantley. “Leveritt sues over legal discipline gag orders.” Arkansas Times. Nov 8, 2011. http://www.arktimes.com/ArkansasBlog/archives/2011/11/08/leveritt-sues-over-legal-discipline-gag-orders

[20] Max Brantley. “Dustin McDaniel puts WM3 call on prosecutor.” Arkansas Times. Aug 19, 2011. http://www.arktimes.com/ArkansasBlog/archives/2011/08/19/dustin-mcdaniel-puts-wm3-call-on-prosecutor

[21] Mark was a prime suspect for years as well, in the public eye, if not in the eyes of the police force with whom he had a long history, both as a domestic abuser, petty criminal, and an informant. [Leveritt] Pam, when still “Hobbs,” originally sued filmmakers Berlinger and Sinofsky after they included in their documentary graphic photos of the crime scene and victims, which Hobbs understood would not be shown. See the oddly-titled Associated Press article, “Mother of slain boy sues in West Memphis film,” published May 17, 1997.

[22] “Parents: No Oscar nod for film about Ark. killings.” Washington Times / Associated Press. 1 December 2011. http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2011/dec/1/parents-no-oscar-nod-for-film-about-ark-killings/

[23] Moreover, the story was inaccurate, stating that “their sentences were set aside and they pleaded guilty to lesser charges,” though it goes on, later, to correctly state that the WM3 “entered their pleas under a legal provision that allowed them to maintain their innocence while acknowledging that prosecutors had enough evidence to convict them.”

[24] The Moores’ statement is from “Parents: No Oscar nod for film about Ark. killings.”

Berlinger and Sinofksy believe the Moores misunderstand their intentions. Ironically enough, in 1993, after hearing about the breaking case, the documentarians assumed that Damien and Jason and Jessie were guilty. Berlinger and Sinofksy traveled to Arkansas intending to make a movie about three depraved and indifferent teenagers and the suffering they had inflicted on a small town. In the beginning, Berlinger and Sinofsky knew even if their film never managed to “protect” children, it would certainly document the horror that some children are capable of perpetrating against other children. [Citation: interviews.]