TRUE CRIME

TRUE CRIME

Introduction

A true story has neither a beginning nor an end. It expands in all directions at once, in cycles, if not circles, in which we may discern any number of patterns that repeat. The concepts of past and future are linguistic conveniences to describe a uniquely human error in perception — a psychological condition with no basis in physics — a persistent hallucination, for lack of a better term.

There are no straight lines, no simple linear progressions, except where they are imposed by characters or authors. Examined closely, alleged straight lines are neither straight nor lines. They zag where they should zig. They surprise by revealing dimension. An apparent single beam of light reveals itself as discreet packets of information.

Every event has countless causes, while the so-called event itself can be viewed as a boundless intersection of smaller events. In 1973, for example, my neighbor is murdered shortly after I am born. Local law enforcement refuses to arrest her killer(s). When I’m molested by the Town Constable eight years later, in 1981, the World Trade Center is brand new, and more than three times as many wild animals exist on our planet than exist here today. Common literary and psychological concepts such closure, resolution, etc — to say nothing of justice — may be missing entirely from a true story.

Thus the author of a true story, faced with such difficulties, must ask forgiveness for employing certain convenient fictions such as a beginning or an end — while the author of a true crime further requires pseudonyms and occasional alterations to identifying details. The chief difficulty of the true-crime genre, of course, is that it has no characters, only real people whose hearts are figuratively and literally broken.

Barbara Gibbons

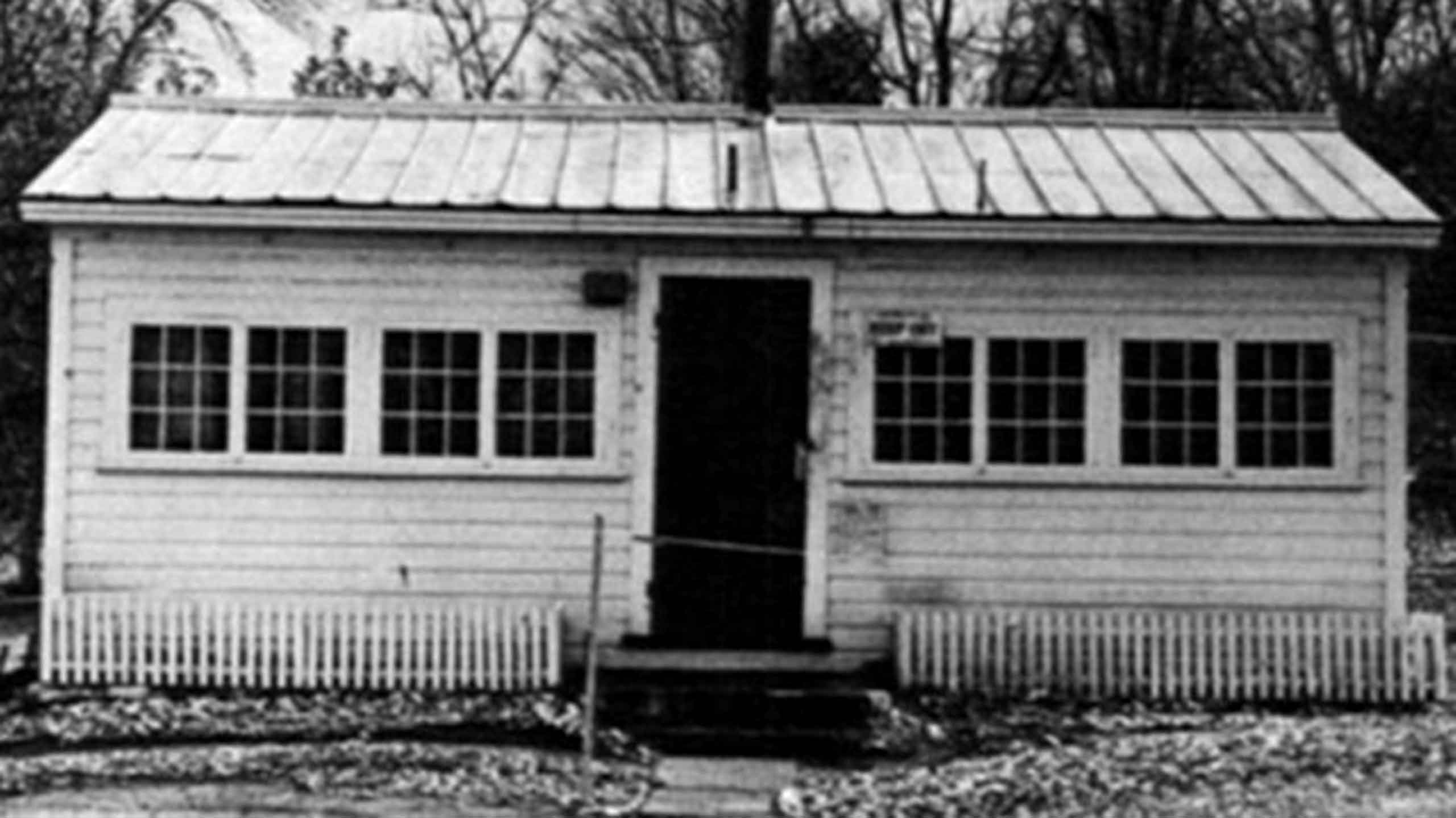

In the autumn of 1973, in the rural northwestern corner of Connecticut, a couple miles up the road from my family’s home, Barbara Gibbons was beaten, raped, and stabbed to death in her tiny cabin on the edge of a swamp. On the evening of 28 September, Barbara’s half century of earthly life came to an end that was as abrupt and violent as it was permanent. She left behind overdue library books. She left behind a teenage son.

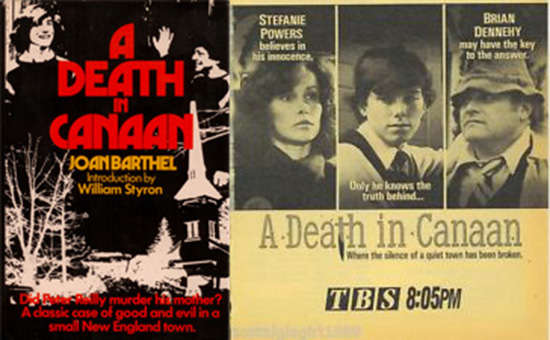

For everyone outside of our small community — and for local children too young to have known Barbara when she was alive — her story seemed to begin with her death. Books would be written. A movie would be made. Because police botched the case. Barbara’s son was wrongfully convicted and later freed. The real killer — or killers — got away.

From my earliest days on this earth I have been haunted, not only by Barbara’s last minutes, but by the very woods of Litchfield County, which seemed to swallow her screams that night. Her neighbors, all of twenty yards away, heard nothing. Heard cicadas and frogs, maybe an owl, as Barbara was bludgeoned and slashed.

The exact sequence of the attack is unknown, however, and it’s possible that Barbara had no chance to scream. The gashes to her neck were deep enough to expose her vocal cords. The bones of her face were shattered. Her ribs were broken. Even her thigh bones.

Some of her wounds — such as violent penetration of her sexual organs “with an unknown object” — were determined to be post-mortem. Barbara’s killers were not satisfied by murder alone; they felt a need to humiliate and desecrate her body even after her death.

The aftermath of this crime, and the mystery that surrounds it, have shaped my understanding of the place I call home—the land where I was born, the land where three centuries of my family have lived and died—seeding questions in my childhood that I could not even articulate until I was older: questions about intersections of the visible and invisible worlds; about the stories we tell in order to revise the lives we live; about the difference between concrete evidence and captivating theories; about which truths must be hidden away — in the trees, along some quiet stretch of river, in some shady knoll, or maybe buried deep inside the earth — in order to preserve a postcard image of a quaint New England community.

Joan Barthel’s book was the first, and Donald Connery’s Guilty Until Proven Innocent is the most comprehensive examination of the case.

I learned to read and write very early, and although I can’t say for sure — memory being such a malleable thing — I’m fairly certain that Joan Barthel’s novel about Barbara’s murder, A Death in Canaan, is the first book I ever read. Every aspect of it captivated me: the authoritative nature of a hardcover, its frightening blood-red title and inverted black-and-white images, all of which promised a story that would explain, in the words of a professional journalist from New York City, what exactly had transpired in my little corner of Connecticut.

Nearly five decades later, however, Barbara’s case remains officially unsolved. And although we locals like to believe that we know who took her life, the only thing certain is who that person was not.

Peter Reilly

Barbara’s son, Peter Reilly, age eighteen and attending a local youth group at the time of her attack, had the dire luck of returning home within just minutes of his mother’s death. For the next twenty-four hours, police interrogated him. He had no blood on his clothes and had called paramedics and police and neighbors as soon as he found his mother, but he was polygraphed nonetheless, then told (wrongly, on purpose) that he had failed the test. The police convinced him that he couldn’t remember killing his mother because he had blacked out, and by the end of the interrogation, the traumatized teen had “confessed” — complete with “details” of the crime that didn’t actually match any the evidence at the scene.

Police had no experience with false confessions at the time, because it was Peter’s confession that would bring the phenomenon to national attention. Today Peter’s case is discussed in every Criminology 101 textbook and class — but in 1973, Peter’s case was not a study, not a story, not a cautionary tale; it was no more and no less than Peter’s life. Despite a room full of alibis, and despite the lack of blood on Peter’s clothes, and despite later evidence pointing to a pair of young men who lived nearby, Peter was tried and convicted in Superior Court in Litchfield, Connecticut — a town that is home, ironically, to the oldest law school in the United States.

Peter’s later exoneration was hastened by celebrity involvement and pressure, but only the court system itself can reopen a prisoner’s cell door. Peter was eventually freed for one reason alone: the State’s prosecutor died of a heart attack — leaving behind all the exculpatory evidence that he had withheld from the defense.

Authorities

Eight years after Barbara’s murder, in 1981, I was molested by a male police officer — our town constable — who lived next door to me.

I was a budding entrepreneur at the time, smart enough to capitalize on childish cuteness, so I spent my weekends towing a red wagon around town, out of which I sold pens, stationary, and sundry office supplies.

Earning money was only part of the joy. I was making my mark on the world, carving out my destiny — all at eight years old. My parents were not worriers and gave me license to travel far and wide, so long as I was home in time for dinner and did my best not to get run over.

Which is why I didn’t bother going to the constable’s house until several months into my business excursions — his house was literally next door; it held no sense of adventure. I saw his wife every day. She was my school librarian.

Eventually, however, having already bled dry every other neighbor within walking distance, I finally knocked on their door. My librarian answered. She told me to come back on the weekend, when her husband would be home.

She was the quiet type (of course), and in hindsight I can only speculate that watching was her thing. The day I returned, she actually baked cookies and otherwise puttered around the kitchen while her husband, just a few feet away, molested me at their breakfast table.

When it was over, I went home with a mild stomach ache and the sense that I’d been involved in something that wasn’t right. I wasn’t traumatized; I was baffled. I told my mother what happened. She told me that the constable was a “dirty old man” and that I should stay away. End of lecture.

To this day I remain grateful that my mother did not involve social services, let alone involving the constable’s friends in law enforcement. For my part, I told no one else until I was an adult. Neither the constable nor the school librarian were ever charged with crimes. I don’t know how many other children they molested. I know only that their son, who was several years older than me and became a librarian at a nearby college, was later arrested — by police in a different county, with no allegiance to his father — for possession of child pornography.

Panic

Beginning in the 1980s, child sexual abuse became a national media concern, featured in nightly newscasts and on daytime talkshows alike. Prosecutions for “child-sex rings” and “ritual abuse,” even “satanic ritual abuse,” also began to make headlines. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, prosecutions for these alleged crimes led to several hundred people being sentenced to lifetimes in prison — and most of them were innocent.

At the time these cases were unfolding, few people in the U.S. questioned either the media reports or the prosecutions they covered. An era glibly referred to now as the “Satanic Panic,” these dark days were indeed my formative years as a writer, influencing my work both then and now.

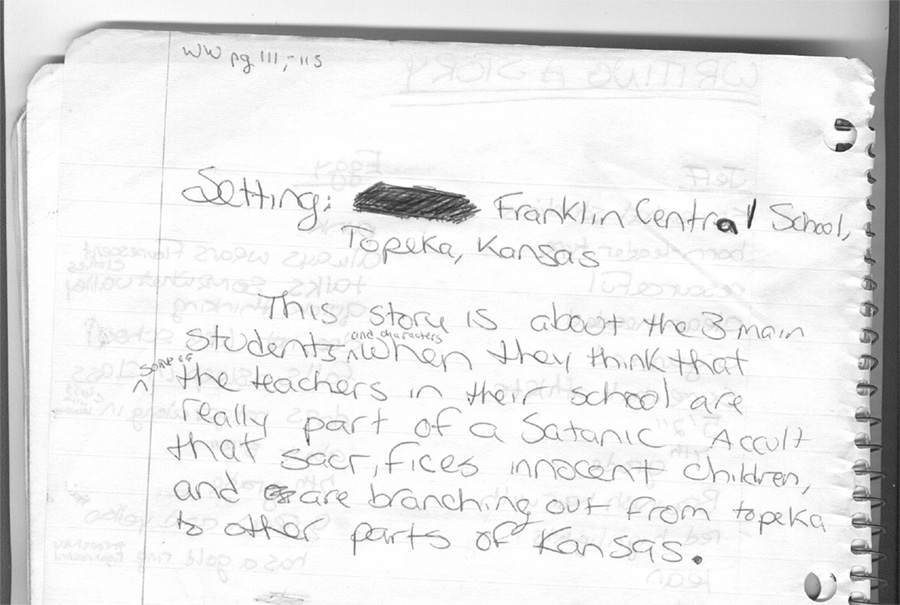

The author’s synopsis for his 5th-grade short story: “School of Satan,” which shocked his teacher less for its content and more for requiring her to read over 20 pages (while adding “Satanic Accult” to the lexicon, apparently). Fellow historians of the Panic will note the coincidence of the use of name “Franklin” here, several years _before_ the now-infamous Franklin child prostitution ring allegations. (Note, too: although the author’s story in centered in Kansas rather than Nebraska, the two cornfield states might as well have been the same, in the mind of this Yankee author at age 10.)

Despite my own victimization as a child, I am more interested in wrongful prosecutions for child sexual assault, most of which use variations on the same methods that were effective in the 1980s. Today prosecutors are less likely to invoke the specter of diabolism, specifically, but they are also less likely to need to do so. What was “shocking” about child-sex crimes in the 1980s and early 90s is now taken for granted: juries today have little trouble believing that every priest, every teacher, every Scout leader, et al, is a secret pedophile, despite the statistical rarity of pedophilia; just as television would have us believe that the abduction and murder of children is a near daily occurrence in the U.S., despite the fact any given child here is approximately as likely to be struck and killed by lightning. Lastly, with the recent proliferation of conspiracies such as QAnon, Flat-earthers, and their ilk, it is clear that the many in the U.S. can no longer discern fact from fiction. If a jury has no use for science or even the historical record, they are unlikely to have much use for evidence, let alone quaint notions of due process, etc.

The Law in Litchfield County

In 2003, out of fear that authorities would soon discover the incest in their home, a husband and wife in Sharon, Connecticut claimed that their neighbor, seventeen-year-old Jeremy Barney, had beaten, tortured, raped, and sodomized all three of their children, as well as their family pets, over a period of several years. The parents alleged that Jeremy had tortured the children psychologically and physically — including bizarre, seemingly ritualistic attacks involving bondage, sexual prosthetics, and wine — in addition to more routine attacks with a baseball bat, knife, and shards of glass. Despite the extreme violence of the alleged assaults, the parents claimed to have been unaware of them because they occurred only when Jeremy was employed to babysit.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the State’s forensic medical examinations of the children would later refute the parents’ claims — while corroborating non-violent incestuous molestation. Further interviews with the parents and children served only to contradict each other and the known facts.

By then, however, it was too late. Social services, law enforcement, and the State’s Attorney had already committed themselves to the family’s fabrications. As frequently happens in wrongful cases, the prosecution simply refused to admit they had gotten the case all wrong. Rather than jeopardize their careers, they chose instead to send a teenager to maximum-security prison for twenty years.

It so happens that Jeremy Barney is my sister’s only son. My only nephew.

It so happens, too, that Jeremy’s case and the Barbara Gibbons / Peter Reilly case of 1973 share remarkable similarities. In addition to unfolding exactly thirty years apart, each case was investigated by the same small police department, whose detectives would botch the job by focusing on one suspect while all actual evidence pointed elsewhere. In each case, the suspect was a gentle, skinny, bespectacled white male in his senior year at Housatonic Valley Regional High School, who would be interrogated and polygraphed and badgered relentlessly in the absence of a so much as a friendly adult, let alone an attorney. And with no money to mount a proper defense, each kid would soon find himself wrongfully convicted in Litchfield Superior Court.

And in each case, most importantly, the prosecution committed gross misconduct, withholding exculpatory evidence and sacrificing the health and futures of other people — teens and children, specifically, to say nothing of justice for a murdered woman — for no reason other than protecting their own careers.

To this day, in fact — despite Peter Reilly’s exoneration by the same judge who’d convicted him, the only authority involved to admit a “grave injustice” — the official stance of the Connecticut State Police is that they caught the right man kid in 1973. For almost fifty years now, they have refused to admit they got everything wrong. To think that they would ever admit wrongdoing in a case so “recent” as Jeremy Barney’s 2005 conviction — well, it’s simply inconceivable.

As Fate Would Have it

… and as one might expect, the aforementioned incidents have shaped much of my research and writing. The fruits of which are my forthcoming novel, Angela’s Story, primarily, along with various essays on other cases, both active and historical. These include several about the West Memphis Three, partly because the prosecution of that case was a product the same Satanic Panic that informed child-abuse cases of the time, and partly because I was blessed to meet Damien Echols and Lorri Davis and will remain forever inspired by their particular magick and its power to overcome the dark forces they faced in the long years before the release of the West Memphis Three in 2011.

More information on Jeremy Barney and Angela’s Story can be found at their respective links.